Revista Industrial Data 25(2): 91-114 (2022)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15381/idata.v25i2.19887

ISSN: 1560-9146 (Impreso) / ISSN: 1810-9993 (Electrónico)

Creation of Social Value by Amazon Entrepreneurs

María Mercedes Zevallos Castañeda[1]

Submitted: 19/03/2021 Accepted: 14/04/2022 Published: 31/12/2022

ABSTRACT

Social entrepreneurship is a concept often associated with ventures to develop products or services for national or international markets and the social benefits they generate. However, little is known about the impact of social entrepreneurship on indigenous communities such as those found in the Peruvian Amazon. This paper examines social value creation following the implementation of an educational process based on the development of entrepreneurship skills in leaders of multiethnic communities in Loreto, Peru. A quasi-experimental design was used to establish a comparison between an experimental group and a control group. It was found that the leaders of the intervention group outperformed the control group in terms of the promotion of collective learning, a higher level of association and a greater capacity to interact with institutions that support community development.

Keywords: social entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education, social value, skill building.

INTRODUCTION

This paper advances the discussion on whether or not it is possible to develop entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship skills within impoverished people. Against the background of poverty of this population, this analysis is relevant to i) identify the basic principles to promote social entrepreneurship and the process to train social entrepreneurs and ii) promote training programs for social entrepreneurs on a large scale for collective, family and individual benefit.

Based on the results achieved through multiple efforts to train rural and indigenous social entrepreneurs, this paper provides information on the importance of education in the training of entrepreneurs and the social impact they have in their communities of origin.

The identification of the principles for training social entrepreneurs is the basis for a methodological proposal to scale the results to other communities of indigenous groups that experience exclusion.

Therefore, the following research question was raised: Is it possible to develop the skills of entrepreneurial leaders in impoverished areas to create social value and promote the development of their communities? To answer this question, an initiative that promoted the development of skills for social entrepreneurship in leaders of rural communities of the Shawi ethnic group was studied in Loreto, in the Peruvian Amazon. It consisted of implementing a training program for local leaders in 86 communities in the districts of Balsapuerto and Yurimaguas, located in the Paranapura and Cachiyacu river basins, to address local development needs while respecting the environment.

Theoretical Framework

Two concepts were used for the theoretical framework: 1) entrepreneurship and 2) social entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship is related to the identification of opportunities to create profit. Thus, Casson (1982) states that “Entrepreneurial opportunities are those situations in which new goods, services, raw materials, and organizing methods can be introduced and sold at greater than their cost of production” (as cited in Venkataraman & Shane, 2000, p. 220).

Indeed, experiences around the world show that entrepreneurial individuals can also provide solutions to reduce or solve social problems (Bikse et al., 2015). They are characterized by a strong social awareness and a high spirit of entrepreneurship, and can prove to be instrumental in the economic and social development of communities. Among the most outstanding cases worldwide are those of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh and the microcredit companies (Zahra et al., 2009), which managed to solve access to capital problems for low-income families.

A recurring element in the definitions of social entrepreneurship is the determination of entrepreneurs to find solutions to social problems such as environmental, health or access to education problems; however, this cannot be defined as charity, since entrepreneurs are motivated at the same time by the profit that such solutions represent, in other words, “entrepreneurs are business people” (Roberts and Woods, 2005, p. 50).

Finally, before moving on to the definition of social entrepreneurship, a distinction must be made between social entrepreneurship and social activism. Whereas social activists attempt to promote change by influencing other actors (governments, social organizations or others), entrepreneurs take direct action and seek ways to solve problems (Martin & Osberg, 2007, p. 37).

Social Entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurship has been studied and defined by several authors. Fowler (2000) focuses on creativity and the pursuit of social benefits, and defines social entrepreneurship as “the creation of viable (socio-)economic structures, relations, institutions, organisations and practices that yield and sustain social benefits” (649). Including value generation as a characteristic of social entrepreneurship, Dees et al. (2002) postulated that “social entrepreneurship is not about starting a business or becoming more comercial. It is about finding new and better ways to create social value” (p. 121). That same year, Hibbert et al. (2002) included in their definition of social entrepreneurship the use of earnings to benefit social groups at a disadvantage in relation to society as a whole. Similar to this approach are Mair and Noboa (2006), who identify social entrepreneurs “as the innovative use of resource combinations to pursue opportunities aiming at the creation of organizations and/or practices that yield and sustain social benefits” (p. 5).

Lasprogata and Cotten (2003) draw a distinction between social entrepreneurship and for-profit enterprises, stating that “nonprofit organizations that apply entrepreneurial strategies to sustain themselves financially while having a greater impact on their social mission” (p.69). In line with this approach, Brouard and Larivet (2010) propose that social entrepreneurs seek to achieve social value rather than financial value. They define them as individuals with an entrepreneurial spirit and strong personality who act as change agents and leaders to solve social problems. Pomerantz (2003) states that, whether individually or collectively, what defines social entrepreneurship is innovation to achieve a social goal. Roberts and Woods (2005) also identify entrepreneurial characteristics as being visionary and passionate. They assert that social entrepreneurs do not discover opportunities, but rather create them by sharing ideas, evaluating them, and collectively developing solutions that address identified social problems.

Sullivan Mort et al. (2003) consider that the social entrepreneur combines innovation with a clear social objective and leadership skills. Accordingly, the authors propose that social entrepreneurs include “the expression of entrepreneurially virtuous behaviour to achieve the social mission, a coherent unity of purposeand action in the face of moral complexity, theability to recognise social value-creating oppor-tunities and key decision-making characteristicsof innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking” (Sullivan Mort et al., 2003, p. 76).

A more comprehensive concept was devised by Peredo and McLean (2006), who identify several attributes of the social entrepreneur, stating that the social entrepreneur

(1) aim(s) at creating social value, either exclusively or at least in some prominent way; (2) show(s) a capacity to recognize and take advantage of opportunities to create that value (“envision”); (3) employ(s) innovation, ranging from outright invention to adapting someone else’s novelty, in creating and/or distributing social value; (4) is/are willing to accept an above-average degree of risk in creating and disseminating social value; and (5) is/are unusually resourceful in being relatively undaunted by scarce assets in pursuing their social venture. (p. 64)

Cochran (2007) defines social entrepreneurs based on the way they act and states that social entrepreneurship involves “applying the principles of business and entrepreneurship to social problems” (p. 451). Martin and Osberg (2007) reflect on the process that the social innovator should follow, which includes three components:

(1) identifying a stable but inherently unjust equilibrium that causes the exclusion, marginalization, or suffering of a segment of humanity that lacks the financial means or political clout to achieve any transformative benefit on its own; (2) identifying an opportunity in this unjust equilibrium, developing a social value proposition, and bringing to bear inspiration, creativity, direct action, courage, and fortitude, thereby challenging the stable state’s hegemony; and (3) forging a new, stable equilibrium that releases trapped potential or alleviates the suffering of the targeted group, and through imitation and the creation of a stable ecosystem around the new equilibrium ensuring a better future for the targeted group and even society at large. (p. 35)

For Guzmán and Trujillo (2008) social entrepreneurship is defined as a venture that

busca soluciones para problemas sociales a través de la construcción, evaluación y persecución de oportunidades que permitan la generación de valor social sostenible, alcanzando equilibrios nuevos y estables en relación con las condiciones sociales, a través de la acción directa llevada a cabo por organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro, empresas u organismos gubernamentales [seeks solutions to social problems based on the building, evaluation and pursuit of opportunities that allow the creation of sustainable social value, achieving new and stable balances in relation to social conditions, through direct action carried out by non-profit organizations, companies or government agencies. (p. 110)

Zahra et al. (2009) identify the pursuit of opportunities as a characteristic of the social entrepreneur, but so is wealth creation. Furthermore, Bikse et al. (2015) focus their attention on the characteristics of the individual and state that

It is a person with a rich imagination and wide vision, who is goal-oriented and loyal to an idea. His/her mission is the creation of social values, distinguishing new, innovative possibilities for the implementation of a social mission. Energetic, enthusiastic and determined to act tenaciously, confidently and with responsibility in order to achieve final results. The profit gained serves as a means for the realisation of social aims. (p. 473)

Upon analysis of the most relevant concepts, there are six elements that agree on the definition of the social entrepreneur. The first element refers to the impact on social issues, the second concerns the performance in a given context characterized by poverty, the third is related to the personality traits of the individual (passionate, enthusiastic, reliable, innovative), the fourth is associated with the role assumed as an agent of change in social spaces, and the fifth element involves the motivation of the social entrepreneur, which is based not so much on economic gain as on the social gain or value associated with the activity performed.

From the literature it is clear that in order to create social value, trust among actors is essential for exchanging knowledge and implementing innovation processes; in this sense, a sixth element becomes apparent: social capital, which depends on connections and relationships between people and organizations, networks and institutions, which in turn foster learning and collaborative innovation (Conceição et al., 2001).

Social Value

From the above, social value relates to the profit that can be distributed among the members of the community, noting that although, at the beginning, these benefits may be of an individual nature, later they acquire a community or collective nature. Guzmán and Trujillo (2008) provide a concept of social value, to which we adhere, as the identification and removal of various obstacles that affect the inclusion of people in economic activities. The recipient of social value can access goods that were previously beyond his or her reach.

Three defining characteristics of social entrepreneurship are identified: 1) they are committed to their community, 2) they aim to promote collective learning, and 3) they involve other members of the community in the work and the profit of the venture.

METHODOLOGY

Methodological Process

The process used in the research is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Methodological Process.

|

Parts |

Activity |

Sub-Activity |

|

Part One: Literature review |

1. Literature review |

Review of the theory of social entrepreneurship and the characteristics of social entrepreneurs. |

|

2. Identification of the characteristics of the social entrepreneur |

The research problem, the hypotheses and the variables to be studied are proposed. |

|

|

Part Two: Data collection |

1. Elaboration of a questionnaire for the systematization of information |

A semi-structured interview guide was prepared to systematize the experience of training social entrepreneurs. |

|

2. Elaboration and validation of a survey questionnaire and delimitation of the study population (control group and experimental group) |

Based on the variables defined, the questionnaire for the quasi-experimental study was prepared. |

|

|

3. Collection of contex information through systematization |

A series of interviews were conducted to collect information about the venture. |

|

|

4. Collection of data using survey questionnaires applied to the control and the experimental group |

Data was collected using survey questionnaires administered to the participating communities, the experimental group and the control group(32). |

|

|

Part Three: Analysis and validation |

1. Data processing |

Data was organized according to the characteristics of education in social entrepreneurship. |

|

Data from the survey questionnaires was processed using statistical correlation for validation. |

||

|

2. Data validation |

A comparative analysis was performed using the information obtained from the survey questionnaires administered to the experimental and the control group. |

|

|

3. Identification of basic principles for an educational process in social entrepreneurship |

Conclusion of the research and identification of any limitations. |

Source: Prepared by the author.

The dependent variable analyzed was the “creation of social value”. For its measurement, the three elements identified in the performance of a social entrepreneur were taken into account: a) social commitment to his or her community, b) promotion of collective learning, and c) involvement of other community members in the work and profit-sharing.

Table 2 provides details of the variable, the three operational definitions and the indicators used for measurement.

Table 2. Variables and Indicators.

|

Variable |

Operational Definition (means of measuring the variable) |

Indicator |

|

Measurement of Social Value Creation

|

Social commitment with your community |

Identify care activities undertaken in your community. |

|

Determine if you have sought alliances to promote community development. |

||

|

Promotion of collective learning |

Determine if knowledge has been relayed to other people. |

|

|

Involvement of other community members in the work and profit-sharing |

Determine if projects or businesses have been implemented jointly with members of the community. |

Source: Prepared by the author.

A quasi-experimental design was used in this study, i. e., a comparison between an experimental group and a control group. The experimental group consisted of leaders of Amazonian communities that have engaged in activities to promote social entrepreneurship with local development proposals and have promoted the training of leaders with characteristics of social entrepreneurs. This group was already formed before the research, thus its existence is independent of the experiment.

The control group consisted of Amazonian community leaders who are not members of the Federación Multiétnica Unidos por la Amazonía [FMUA], but rather belong to other organizations and live in rural areas of the Peruvian Amazon in Loreto, within the same area of the Paranapura and Cachiyacu river basins.

Sampling

The sample size was determined based on the minimum value proposed by Hernández and Mendoza (2018) and taking Gall et al. (1996) and Mertens (2019) as a reference. According to these authors, the minimum sample for the quasi-experimental design is 15 people. A description of the sample for the control and experimental groups, with 24 leaders for each of the cases, is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Description of the Experimental and Control Groups.

|

Description |

Name |

|

24 Amazonian leaders from rural communities members of the Federación Multiétnica Unidos por la Amazonía. The sample was non-probabilistic as typical cases were chosen. |

Experimental group |

|

24 Amazonian leaders from communities in the Peruvian Amazon that are not members of the Federación Multiétnica Unidos por la Amazonía. The sample was non-probabilistic since typical cases were chosen. |

Control group |

Source: Prepared by the author.

Sample Selection

Four criteria listed in Table 4 were used; the only difference between the groups was whether or not they belonged to the Federación Multiétnica Unidos por la Amazonía.

Table 4. Criteria for Sample Selection.

|

Criteria |

Experimental Group |

Control Group |

|

Member of the Federación Multiétnica Unidos por la Amazonía |

Yes |

No |

|

Recognized leadership in their communities |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Lives in rural Amazonian communities |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Lives in the Paranapura river basin |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: Prepared by the author.

Instrument and Data Analysis

Both the intervention and control groups were administered a survey questionnaire[2]. The reliability of the instrument was assessed by means of Cronbach’s alpha (α), obtaining a coefficient of 0.816, which is within the range of reliability. Values of alpha greater than 0.7 or 0.8 are considered sufficient to ensure the reliability of the instrument.

Data Collection

The data collection was conducted from July 16 to 30, 2017. Sixteen communities were visited to assemble the sample for the experimental group and 16 communities were visited for the control group. From these communities, a sample of 31 leaders was selected for the control group and 30 leaders for the experimental group, alternating men and women in each group.

RESULTS

Systematization of the Case Study

The study area is home to a multi-ethnic population, with a predominance of the Shawi ethnic group, and this is where the capacity building project began in 1999, when the Apostolic Vicariate of Yurimaguas entrusted the Missionaries of Jesus with the pastoral care of the area. Efforts have been permanent and constant, promoting sustained development processes that have made improvements in education, health, defense of rights, support for the development of entrepreneurial skills and social development, always promoting the active participation of the community (Vélez, 2017).

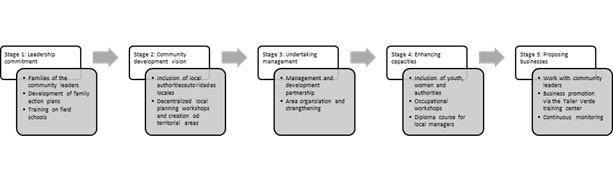

The project timeline has five stages that are presented in Figure 1 and summarized below.

Figure 1. Intervention Stages.

Source: Prepared by the author.

During the first stage (1999 to 2002), a program named “Salud para Todos” [Health for All] was launched, promoted by the Vicariate of Yurimaguas with the support of the Catalan NGO “La Liga de los Pueblos”. The program attempted to combat malaria by training health promoters. Despite achieving the objectives, it became evident that in order to achieve the comprehensive development of the area, it was necessary to identify and address the structural problems of the population (poverty, lack of basic services, food security, among others). If structural problems were not addressed, the living conditions of the population would not change and health would not improve. At this stage, community leaders and their families participated and family action plans were developed in the so-called “field schools”.

During the second stage (2005 to 2006), a training program for community leaders was designed and implemented, integrating local authorities and prioritizing issues related to human development and health promotion. Special emphasis was placed on building a community vision towards development, which also included planning themes and methodologies and the definition of territorial zones to facilitate the process (Alto Paranapura, Bajo Paranapura, Medio Paranapura, Alto Cachiyacu and Bajo Cachiyacu).

During the third stage (2007 to 2011), the program Desarrollo de Capacidades de los Pueblos Amazónicos [Amazon Peoples Capacity Bulilding] (DECA) was launched, aimed at developing leaders’ capacities for territorial management and the creation of an organization representing the communities located in the basin called Federación Multiétnica de Comunidades del Paranapura Unidos por la Amazonía. At this stage, a territorial management course was conducted with the Escuela Mayor de Gestión Municipal, led by Michel Azcueta[3].

The fourth stage (2012 to 2016) aimed to achieve community support for the leaders and the FMUA, as well as to strengthen the concept of entrepreneurship-based development. At this stage, entrepreneurship workshops in carpentry, mechanics and sewing were implemented in collaboration with the leaders. The leaders acquired knowledge and disseminated it in their communities. The purpose of this was to strengthen and legitimize the leaders’ representativeness in their respective communities.

Finally, during the fifth satge (2017 to 2020), economic ventures with a vision of sustainable and responsible use of resources, with a commitment to preserve diversity and the environment, were undertaken jointly with a group of young leaders. Support for this stage was provided by Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, which conducted a workshop on entrepreneurial methodologies via the Incubadora de Empresas 1551 [1551 Business Incubator]. In 2020, these young people created a brand called “Taller Verde” [Green Workshop] that commercializes chocolate, essential oils and wooden toys, with a focus on respect for the environment.

Hypothesis Validation

The null hypothesis (H0) states that the mean obtained by the experimental group is equal to the mean of the control group.

The alternate hypothesis (H1) states that the mean obtained by the control group is different from the mean of the experimental group.

Clearly, this is a case of a comparison between two independent populations. Entering the values of the intervention and control group samples into the SPSS, the following results are obtained:

Table 5. Group Statistics - Creation of Social Value.

|

Group |

N |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

SE of Mean |

|

Experimental |

31 |

4.29 |

1.367 |

.279 |

|

Control |

30 |

3.07 |

1.184 |

.224 |

Source: Prepared by the author.

It can be observed in Table 5 that the mean of the perceptions of the explerimental group is higher than that of the control group.

The Mann-Whitney U test was used for the test statistics. The Student’s t-test is often used for continuous distributions when two different populations are to be compared; however, in the case of this study, since it is a non-continuous distribution, non-parametric procedures or techniques must be used.

The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test or Mann-Whitney U test can be used to evaluate two independent groups drawn from the same population, provided that data on the variables under study have been obtained on an ordinal scale at least. As one of the most powerful nonparametric tests, it is a fairly good alternative to the parametric t-test when the researcher wishes to avoid the assumptions of the t-test or when the research measurements are on a scale below the interval scale (Siegel & Castellan, 1972).

Table 6. Test Statisticsa – Creation of Social Value.

|

Mann-Whitney U |

177.000 |

|

Wilcoxon W |

583.000 |

|

Z |

-3.041 |

|

Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) |

.002 |

|

|

|

a. Grouping Variable: VAR00002

Source: Prepared by the author.

As shown in Table 6, the p-value corresponds to the asymptotic significance, where p = 0.002 < 0.005; therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected and the alternative hypothesis is accepted. It is then concluded that the experimental group creates greater social value than the mean of the control group.

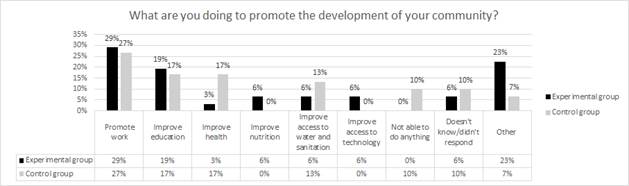

Social Commitment to their Community

The first element related to the variable whether there is a social commitment of the leader to the community. Two indicators were used to measure it: a) the identification of activities to promote the development of their community and b) the identification of alliances to promote community development. Regarding community care activities, we asked about the actions taken by the leader (experimental and control groups) to promote the development of his/her community (Figure 2). In both cases, the experimental group leader had a higher response than the control group leader; however, it was not relevant. Results for both cases (experimental and control groups) show that the leader promotes work and seeks to improve education. Concern for improving health and access to water and sanitation are predominant in the control group. The response “there is nothing they can do”, which appears as a rate only in the control group, is relevant. This suggests that the experimental group leaders have a better self-perception of their role as agents of change in the community.

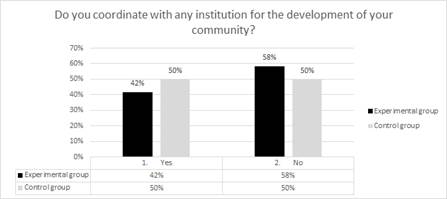

As for the establishment of alliances to promote community development, they were measured in terms of the institutional collaborations achieved. As shown in Figure 3, it was found that the leaders of the experimental group coordinated with other institutions on a smaller number of occasions than those belonging to the control group.

This result suggests that the experimental group leaders have had access to a broader social network, therefore, they have greater opportunities to relate with others. In the case of the control group leaders, the obtained result could be related to a lack of trust in the institutions and a commitment to development that stems from themselves, in other words, to a greater independence in taking action in favor of the community.

Figure 2. Actions for Community Development.

Source: Survey questionnaire.

N: 24 experimental group leaders and 24 control group leaders.

Figure 3. Coordination with Institutions.

Source: Survey questionnaire.

N: 24 experimental group leaders and 24 control group leaders.

Creating Social Value through the Promotion of Collective Learning

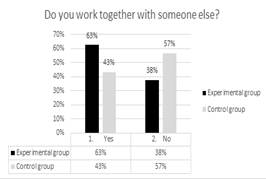

The second element related to the variable is whether there is a willingness for collective learning. The indicator used consisted of identifying whether there is a tendency to work with other people in the community and whether knowledge is conveyed to other people in the community. Questioned in relation to working together with others, the experimental group leaders showed a greater tendency to work together in pairs with another person in the community (Figure 4). More specifically, 63% of the experimental group leaders reported doing so, compared to the 43% of the control group leaders.

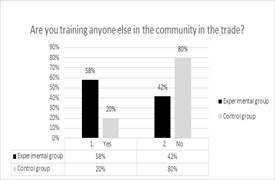

Data was also collected on whether they teach a trade to other people in the community. The experimental group leaders that had been intervened showed a greater predisposition to teach other people and share the knowledge acquired in 58% of the cases (Figure 5). For the control group leaders, this percentage amounted to 20%.

|

|

|

|

Figure 4. Work with another person in the community. |

Figure 5. Share knowledge about the trade. |

Source: Survey questionnaire.

N: 24 experimental group leaders and 30 control group leaders.

Involvement of Other Community Members in the Work and Profit-Sharing

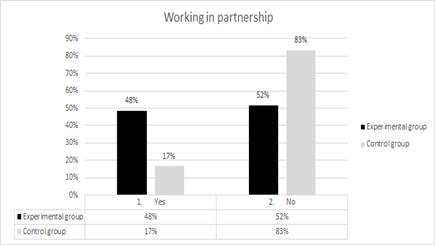

The third element related to the creation of social value was the involvement of other community members in the work and profit-sharing. The indicator used consisted of identifying whether joint projects or businesses have been implemented with members of the group with whom they participate in various workshops. The results show that half of the experimental group leaders have conducted business with other members of the group with which they have been trained. This percentage was much lower in the case of the control group, which reached only 17% (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Working in Partnership.

Source: Survey questionnaire.

N: 30 experimental group leaders and 31 control group leaders.

DISCUSSION

As for the variable whether there is a social commitment of the leader with the community, for both the control group and the experimental group, there is a concern for the improvement of health, access to water and access to sanitation. In both cases a concern for collective benefit is suggested, which is the basis of social entrepreneurship as can be reviewed in the various existing concepts set forth by Bagus and Manzilati (2014).

The difference in the experimental group, however, is the better self-perception of the entrepreneur’s role as a development agent in the community and the building of networks, the establishment of alliances and/or the greater frequency of interaction with institutions that can contribute to community development. Regarding self-perception, previous studies have focused on the personality of the social entrepreneur and his or her particular skills as a key element for the development of entrepreneurship. The literature suggests that special leadership skills (Thompson et al., 2000) based on a vision (Bornstein, 1998) are two of the characteristics of social entrepreneurs.

Regarding alliances, the study conducted in the Peruvian Amazon corroborates the findings of Bhagavatula et al. (2010), who demonstrated that the networks established within the loom weaving communities in India had an impact on mobilizing greater resources and access to business opportunities. In this study conducted in the Peruvian Amazon, the results suggest that the experimental group leaders have had access to a broader social network and therefore have greater opportunities to relate with others, either private companies or public institutions, establishing forums where decisions can be made and consensus can be built for local development.

Regarding the existence of a willingness for collective learning, the experimental group showed a clear tendency to work with others in the community or to teach other people the acquired knowledge. The results also show that they have been inclined to do projects together with other people in the community. Both establish a relationship with the concept of social entrepreneurship, understood as performing social activities that generate profits that are then distributed as an effort for the creation of social value and which is referred to by Bagus and Manzilati (2014). These benefits can be individual or collective and in this case refer to knowledge and skills to execute, undertake or manage.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the initial hypothesis that the experimental group leaders who participate in the UPA create more social value in their community than those in the control group is accepted. The experimental group leaders performed better than the control group leaders:

· They promoted collective learning to a greater extent, as they showed a greater predisposition to work with another person and to share the knowledge of their trade with another person in the community.

· They showed a greater interest in associating with members of the educational community in which they participate and in sharing the profit obtained.

· They showed a greater capacity to coordinate with institutions that could support the development of their communities.

The variable that differentiates the experimental group from the control group is having participated in an educational process promoted by a civil society entity (the Catholic Church) with the support of a variety of allies in the absence of the State. This process complied with five basic principles for social entrepreneurship, which are listed below:

1. Use a methodology based on trial and error that allowed for a learning-by-doing process, constant and systematic reflection and openness to change.

2. Establish alliances with various institutions, particularly with civil society.

3. Guarantee the sustainability of the processes through its own resources. Work was not stopped at any time.

4. Identify the skills of the population/leaders as a starting point and as a constant practice.

5. Start from the culture of the leaders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to give special thanks to Jorge Vélez, advisor to “Unidos por la Amazonía”, and to all the leaders of the communities of the Paranapura river basin. A special mention to PhD Oscar Tinoco of the School of Industrial Engineering of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos for his feedback and remarks, part of an ongoing mentoring.

REFERENCES

[1] Bagus, A., & Manzilati, A. (2014). Social Entrepreneurship and Socio-entrepreneurship: A Study with Economic and Social Perspective. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 115, 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.411

[2] Bhagavatula, S., Elfring, T., Tilburg A., & Van de Bunt, G. (2010). How social and human capital influence opportunity recognition and resource mobilization in India’s handloom industry. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(3), 245-260.

[3] Bikse, V., Rivza, B., & Riemere, I. (2015). The social entrepreneur as a promoter of social advancement. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 185, 469-478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.405

[4] Bornstein, D. (1998). Changing the World on a Shoestring: An ambitious Foundation Promotes Social Change by Finding Social Entrepreneurs. The Atlantic Monthly, 281(1), 34-39.

[5] Brouard, F., & Larivet, S. (2010). Essay of Clarifications and Definitions of the Related Concepts of Social Enterprise, Social Entrepreneur and Social Entrepreneurship. En A. Fayolle y H. Matlay (Eds.), Handbook of research on Social Entrepreneurship. Cheltenham, Reino Unido: Edward Elgar Publishing.

[6] Casson, M. (1982). The entrepreneur: An economic theory. Lanham, MD, EE. UU.: Rowman & Littlefield.

[7] Cochran, P. L. (2007). The evolution of corporate social responsibility. Business Horizons, 50(6), 449-454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2007.06.004

[8] Conceição, P., Gibson, D. V., Heitor, M. V., & Sirilli, G. (2001). Knowledge for Inclusive Development: The Challenge of Globally Integrated learning and Implications for Science and technology Policy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 66(1), 1-29.

[9] Dees, J. G., Emerson, J., & Economy, P. (2002). Enterprising Nonprofits: A Toolkit for Social Entrepreneurs. Nueva York, NY, EE. UU.: John Wiley & Sons.

[10] Fowler, A. (2000). NGDOs as a Moment in History: Beyond Aid to Social Entrepreneurship or Civic Innovation? Third World Quarterly, 21(4), 637-654.

[11] Gall, M. D., Borg, W. R., & Gall, J. P. (1996). Educational Research: An Introduction. White Plains, NY, EE. UU.:Longman Publishing.

[12] Guzmán, A., & Trujillo, M. (2008). Emprendimiento social – revisión de literatura. Estudios Gerenciales, 24(109), 105-125.

[13] Hernández, R., & Mendoza, C. (2018). Metodología de la investigación: Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. Ciudad de México, México: McGraw-Hill Interamericana.

[14] Hibbert, S. A., Hogg, G., & Quinn, T. (2002). Consumer Response to Social Entrepreneurship: The Case of the Big Issue in Scotland. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 7(3), 288-301. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.186

[15] Lasprogata, G. A., & Cotten, M. N. (2003). Contemplating “Enterprise”: The Business and Legal Challenges of Social Entrepeneurship. American Business law Journal, 41(1), 67-114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1714.2003.tb00002.x

[16] Mair, J., & Noboa, E. (2006). Social Entrepreneurship: How Intentions to Create a Social Venture are Formed. En J Mair, J. Robinson, y K. Hockerts (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship (pp. 121-135). Hampshire, Reino Unido: Palgrave Macmillan.

[17] Martin, R. L., & Osberg, S. (2007). Social Entrepreneurship: The Case for Definition. Stanford Social Innovation Review Stanford. 5(2), 29-39. https://doi.org/10.48558/TSAV-FG11

[18] Mertens, D. M. (2019). Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA, EE. UU.: SAGE Publications.

[19] Peredo, A. M., & McLean, M. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: A critical review of the concept. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 56-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007

[20] Pomerantz, M. (2003). The business of social entrepreneurship in a" down economy". Business- Emmaus Pennsylvia , 25(2), 25–28.

[21] Roberts, D., & Woods, C. (2005). Changing the world on a shoestring: The concept of social entrepreneurship. University of Auckland Business Review, 7(1), 45-51.

[22] Seelos, C., & Mairb J. (2005). Social entrepreneurship: Creating new business models to serve the poor. Business Horizons (48), 241-246.

[23] Siegel, S., y Castellan, N. J. (1972). Estadística no paramétrica aplicada a las ciencias de la conducta. Distrito Federal, México: Trillas.

[24] Sullivan Mort, G., Weerawardena, J., & Carnegie, K. (2003). Social Entrepreneurship: Towards Conceptualisation. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 8(1), 76‑88.

[25] Thompson, J., Alvy, G., & Lees, A. (2000). Social entrepreneurship: A new look at the people and the potential. Management Decision, 38(5), 328-338. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740010340517

[26] Vélez, J. (2017). Recuperando los procesos de participación y empoderamiento: Sistematización del programa desarrollo de capacidades de los pueblos amazónicos Paranapura - Alto Amazonas - Loreto.

[27] Venkataraman, S., & Shane, S. (2000). The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217-226. https://doi.org/10.2307/259271

[28] Zahra, S. A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. O., & Shulman, J. M. (2009). A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.04.007