INTRODUCTION

The current rise in covid-19 cases has prompted the Peruvian State, as well as companies, to enforce policies and procedures in order to contain the spread of the virus.

One of the sectors that has continued to operate since the beginning of the pandemic has been private security, consisting of security agents and supervisors in charge of watching over and monitoring facilities to safeguard property from theft or vandalism. This meant that employees had to comply with new demands, such as wearing facemasks and maintaining social distancing, as well as executing sanitary protocols in the clients’ establishments where the service is provided.

Job demands that do not match the worker’s capabilities, resources or needs may lead to harmful physical and emotional responses, which are referred to as occupational stress. Low risk levels have been found in other studies conducted on stress levels in this sector (Pineda, 2019); however, in the new context of the pandemic, with new protocols such as wearing facemasks, taking temperature, maintaining physical distance, among others, this level could vary and, thus, giving rise to the novelty and importance required to develop this research.

It is also important for the employer to determine the level of occupational stress that workers who perform this activity might experience in order to develop preventive plans to better manage their mental health.

Entre las herramientas validadas en el país para realizar las mediciones de estrés laboral, se cuenta con el Cuestionario de Estrés Laboral OIT-OMS (Suárez, 2013), el cual evalúa el nivel de riesgo de estrés laboral en nuestra población de estudio, de este modo, la investigación es viable.

Among the tools validated in the country to measure occupational stress, there is the ILO-WHO Workplace Stress Scale (Suárez, 2013), which estimates the level of risk of occupational stress in our study population, thus, the research is reliable.

According to the Spanish trade union Unión General de Trabajadores, an in-depth study of risks that originate from insufficient labor organization is necessary. Such situations make stress relevant as it is related to working conditions or factors, even more so if workers are exposed to them for 12 hours, i. e., the working day of a security agent and supervisor in the country.

There is also the biological risk of exposure to covid-19 due to the execution of the new procedures requested by the client, which involves taking the temperature of people entering the facility, in addition to performing other controls, which may trigger additional stressors.

Therefore, control measures to prevent the onset of occupational stress symptoms, which could lead to absenteeism and to the detriment of labor productivity, are of paramount importance.

Justification and Limitations

This research will provide a real and scientific report on each of the work characteristics or work-related factors that increase the probability of developing a set of emotional, cognitive and physiological responses associated with occupational stress in personnel working in the private security sector. It will also allow for the implementation of preventive and corrective measures to reduce the physical and mental overload of the employee, avoiding consequences that affect health, the immediate environment and the work-personal balance.

It also serves as a starting point for reformulating organizational strategies that will enable human resources teams in the security sector to improve work quality and reduce the economic consequences, thereby promoting a reduction in absenteeism, accident frequency and turnover. The main benefits are the incorporation of a culture of self-care within the framework of psychosocial risks, making them visible and improving communication and interpersonal relations, directly impacting the emotional stability of workers and in turn the quality of service provided to the client.

Also, the publication of the results will serve as a preliminary source of data for future research structured under the same approach.

Finally, the limitations of the study include the fact that the study population was comprised of only one private security company, with its own particular characteristics, which may not necessarily be similar in other companies in the same line of business.

General Objective

The study aims to determine the level of occupational stress of the agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima associated with the work-related factors.

General Hypothesis

There is a significant association between the level of occupational stress and work-related factors of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima.

Occupational Stress

Occupational stress definitions are closely related to stress definitions, insofar as the causes of the former are to be found in the relationship with work.

According to the trade union Unión Nacional de Trabajadores [UGT] Andalucía (2009), occupational stress is el proceso en el que las demandas ambientales comprometen o supera la capacidad adaptativa de un organismo, dando lugar a cambios biológicos y psicológicos que pueden situar a la persona en riesgo de enfermedad [the process in which environmental demands compromise or exceed the adaptive capacity of an organism, leading to biological and psychological changes that may place the person at risk of disease] (as cited in Suárez et al, p.107). Moreover, these authors state that these demands, whether due to overwork, anxiety or fear, cause a state of fatigue, both physical and psychological.

The European Commission defines occupational stress as the set of cognitive, emotional, behavioral and physiological responses to certain harmful or adverse situations caused by the organization, the content or the work environment. It is the state of an individual characterized by high levels of distress and agitation, accompanied by a frequent feeling of inability to cope with the situation (Comisión Europea, 2000).

The WHO defines occupational stress as a person’s response to work-related pressures and demands that do not match his or her skills and knowledge, which often contrast personal sufficiency to cope with a given situation (Organización Mundial de la Salud, 2004).

The ILO states that occupational stress is determined by the demands arising at work that do not relate to or exceed the resources, competencies or needs of the collaborator, even if the job demands do not correspond to the worker’s capabilities or when the worker’s skills or knowledge do not match the expectations of an organization (Organización Internacional del Trabajo, 2016).

Stress is considered to be a response that allows the individual to cope with a situation; occasionally, it may motivate him or her to perform certain actions. However, when it comes to occupational stress, external situations beyond the worker’s control cause an imbalance that, combined with the worker’s own traits, may increase the risk to his or her health.

Work-Related Factors

The Ministerio de Trabajo y Promoción del Empleo del Perú (2016) defines labor factors as the set of working conditions or components in the organization where the worker spends his working day, his occupational, which may or may not be satisfactory, which means that these working conditions relate to safety, quality of life and health within the work activity (as cited in De la Torre, 2019).

Condo and Turpo (2019) state that individuals’ work is affected by three sets of conditions: environmental work conditions (temperature, lighting and other occupational agents); time conditions (break periods, work schedule, among others); and social conditions (status, informal organization, etc.).

According to Robbins and Judge (2009), the sources or potential stress factors consist of three categories: environmental elements, including economic uncertainty, political insecurity and technological change; organizational causes, including task demands, role demands and interpersonal demands; and personal factors, including family problems, economic problems and personality. They further note that stress tends to be a cumulative phenomenon; therefore, to determine the total stress level of an individual, it is necessary to group or categorize stress by restrictions, opportunities and demand.

For his part, Chiavenato (2009) argues that there are two main sources of stress at work: environmental and personal causes. On the one hand, environmental causes would be originated by external and situational factors, which include intensive work scheduling, job insecurity, work environment, intense work flow, high pressure and the number and nature of the client, whether internal or external. As for personal causes, these include different characteristics such as little patience, low tolerance for uncertainty, low self-esteem, poor health, poor work and sleep habits, and lack of exercise.

The consequences of stress affect both the employee and the organization. For individuals, the consequences may include depression, anxiety, anguish and various physical repercussions (headaches, cardiovascular ailments, accidents and nervousness). For organizations, the consequences relate to the work quality and workload, increased absenteeism and turnover, more complaints, dissatisfaction, grievances and strikes (Chiavenato, 2009).

Work Environment

The work environment has a significant value in organizations because it plays an important role in improving productivity, working conditions of the internal user, and relations with customers and the way of addressing the market (Serrano, 2004).

Work Schedule

The work schedule refers to the times for entering and leaving the occupational, that has been previously established by the organization and must be respected by the employee; it represents the time distribution of the daily workday (Ezquerra, 2006).

Incentives

An incentive is the payment received by the worker based on his individual or organizational performance; it is the reward received by the worker for his/her recent performance and constitutes an important component of the total compensation (Robbins & Judge, 2009).

Contract Type

A contract is an agreement reached between the worker and the employer, where the former agrees to provide services under subordination to the latter and, in return, the employer provides compensation. The types of contract can be indeterminate, fixed-term and part-time contract (CERTUS, 2021).

Significance of the Task

It is the willingness to work based on characteristics related to personal development such as fulfillment, fairness, sense of effort or mental contribution. It is the meaning that the employee gives to the work, it is of a personal and social nature, and it is performed with great satisfaction (Palma, 2006).

Job Stability

Job stability can be understood as the work relationship with a permanent status, the dissolution of which will depend on the worker and, exceptionally, the employer, due to non-compliance with duties and/or due to events beyond the control of the individuals, which make continuity impossible (Quiñones & Rodríguez, 2015).

Perception of Safety in the Surrounding Environment

According to Hummelsheim et al. (2010), fear of crime is “a response not just to the perceived crime problem, but also to the form, texture and perceived health of the social and political structures” (p. 328); it would therefore be important to study the social determinants associated with the fear of crime in individuals, such as age and sex, considering that they are part of the general structures experienced on a daily basis in their immediate surroundings.

Workload

The amount of work or workload is the set of psychophysical requirements to which the workers are subjected throughout their workday (Condo & Turpo, 2019).

Compensation

Employees have the right to be compensated with a salary of no less than S/ 930.00 (minimum wage) for the performance of their activities in a formal institution. It should be mentioned that wage depends on the position and the type of position the employee applies for (Condo & Turpo, 2019).

METHODOLOGY

A quantitative approach was used for this study, because data collection was used to test the hypothesis by means of statistical analysis. The design was non-experimental, because the context where security agents and supervisors work was not altered at the time of applying the questionnaires. It is correlational, because the association between the variables “occupational stress” and “work-related factors” was measured. It is cross-sectional, because the study was conducted in the year 2021 in the context of covid-19 pandemic.

The sample was comprised of 541 agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima. To identify the variable work-related factors, a data collection form made up of two components, socio-demographic data and work-related factors data, was used. To determine the occupational stress variable, the ILO-WHO Occupational Stress Scale, initially designed by Ivancevich and Matteson and later adapted by Angela Suárez to the Peruvian context in 2013, was used as instrument. This scale consists of 25 questions distributed in seven dimensions: organizational climate (4 items), organizational structure (4 items), organizational territory (3 items), technology (3 items), leader influence (4 items), lack of cohesion (4 items) and group support (3 items), which are measured on a Likert scale.

The reliability of the ILO-WHO Workplace Stress Scale instrument was evaluated in 30 cases using Cronbach’s alpha test, which considers an instrument to be reliable when its values are greater than 0.7. In this case, a value of 0.948 was obtained, thus confirming the reliability of the instrument. As the instrument “Work-related factors” is a data sheet, it was not necessary to validate it.

Chi-square test was used for hypothesis testing to find associations between the variables “occupational stress” and “work-related factors” in the study population. The test was performed for each work-related factor, yielding the the results shown in Table 3. The association between the variables is considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

From the descriptive results, it was observed that 68.4% of the security agents and supervisors are between 40 and 59 years old. All of them are male. A total of 75.6% of the security agents or supervisors are married or cohabiting. In terms of education, 66.0% have a high school education, 22.3% have a technical education (complete and incomplete), and 11.6% have a higher education. A total of 61.6% have 1 or 2 children.

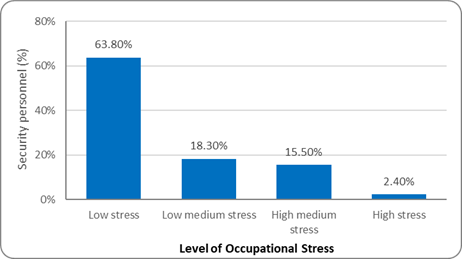

Figure 1 shows the occupational stress level of security agents and supervisors: 63.8% have a low stress level, 18.3% have a low medium stress level, 15.5% have a medium high stress level and 2.4% have a high stress level.

Figure 1. Level of occupational stress of security agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Table 1 shows the descriptive results for group 1 of the work-related factors. It is observed that 82.3% of the security agents and supervisors work in access control with exposure to people and 17.7% do perimeter security without exposure to people. Some 90% of the security agents and supervisors work as security guards, 5.0% work as stand-in guards and another 5.0% work as on call guards. A total of 49.4% security agents and supervisors have been working in a private company for 3 to 10 years; 38.0%, for 1 to 3 years; and 12.6%, for more than 10 years. Of the security agents and supervisors, 81.5% have less than five (5) shift rotations in the private security company; 12.6%, between 5 and 10; and 5.9%, more than 10. In the last year, 52.2% of the security agents and supervisors were supervised daily; 36.4%, weekly; 5.7%, biweekly; and the other 5.7%, monthly. A total of 56.2% of the security agents and supervisors have some form of incentive, 25.7% have no incentive, 13.1% receive a transportation bonus and 5.0% receive a food bonus.

Table 1. Security Agents and Supervisors in a Private Security Company in Lima - Work-Related Factors (Group 1).

|

Work-Related Factors (Group 1) |

N |

% |

|

Type of activity |

||

|

Entrance control with exposure to people |

445 |

82.3% |

|

Perimeter security without exposure to people |

96 |

17.7% |

|

Employment status |

||

|

Permanent employee |

487 |

90.0% |

|

Stand-in guard |

27 |

5.0% |

|

On call guard |

27 |

5.0% |

|

Time working |

||

|

From 1 to 3 years |

206 |

38.0% |

|

3 to 10 years |

267 |

49.4% |

|

More than 10 years |

68 |

12.6% |

|

Shift rotation |

||

|

Less than 5 |

441 |

81.5% |

|

5 a 10 |

68 |

12.6% |

|

More than 10 |

32 |

5.9% |

|

Frequency of supervisions in the last year |

||

|

Daily |

282 |

52.2% |

|

Weekly |

197 |

36.4% |

|

Biweekly |

31 |

5.7% |

|

Monthly |

31 |

5.7% |

|

Incentives |

||

|

Transportation bonus |

71 |

13.1% |

|

Food bonus |

27 |

5.0% |

|

None |

139 |

25.7% |

|

Other |

304 |

56.2% |

|

Total |

541 |

100.0% |

Source: Prepared by the author.

Table 2 shows the results for group 2 of the work-related factors. It is observed that 83.0% of the security agents and supervisors have a 12-hour work schedule; 12.8%, an 8-hour work schedule; and 3.9%, other work schedules. A total of 64.7% of the security agents and supervisors have an indeterminate contract; 26.1%, a semi-annual contract; 8.1%, a quarterly contract; and 1.1%, a monthly contract. In the last month, 51.4% of the security agents and supervisors had a net income (compensation) between S/ 1001 and S/ 1500; 36.8%, between S/ 1501 and S/ 2000; 6.1%, between S/ 500 and S/ 1000; and 5.7%, of more than S/ 2000. Of the security agents and supervisors, 74.9% work in industry; 21.4%, in services; 3.3%, in residences; and 0.4%, in warehouses. Some 64.7% of the security agents and supervisors totally agree with the significance of the task, 29.4% agree, 3.5% totally disagree, 1.8% neither agree nor disagree, and 0.6% disagree. A total of 63.8% of security agents and supervisors have job stability, 17.0% have no job stability, and 19.2% have an uncertain job situation. Finally, 52.9% of security agents and supervisors agree with the perception of security in the surrounding environment, 24.2% strongly agree, 9.2% disagree, 9.1% neither agree nor disagree and 4.6% strongly disagree.

Table 2. Security Agents and Supervisors in a Private Security Company in Lima - Work-Related Factors (Group 2).

|

Work-Related Factors (Group 2) |

N |

% |

|

Working hours |

||

|

8 hours |

69 |

12.8% |

|

10 hours |

2 |

0.4% |

|

12 hours |

449 |

83.0% |

|

Other |

21 |

3.9% |

|

Type of contract |

||

|

Monthly contract |

6 |

1.1% |

|

Quarterly contract |

44 |

8.1% |

|

Semiannual contract |

141 |

26.1% |

|

Indeterminate |

350 |

64.7% |

|

Compensation |

||

|

<500 |

0 |

0.0% |

|

S/ 500 to S/ 1000 |

33 |

6.1% |

|

S/ 1001 to S/ 1500 |

278 |

51.4% |

|

S/ 1501 to S/ 2000 |

199 |

36.8% |

|

More than S/ 2000 |

31 |

5.7% |

|

Type of business where you work |

||

|

Residences |

18 |

3.3% |

|

Industry |

405 |

74.9% |

|

Warehouses |

2 |

0.4% |

|

Service companies |

116 |

21.4% |

|

Significance of the task |

||

|

Strongly disagree |

19 |

3.5% |

|

Disagree |

3 |

0.6% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

10 |

1.8% |

|

Agree |

159 |

29.4% |

|

Strongly agree |

350 |

64.7% |

|

Job Stability |

||

|

Yes |

345 |

63.8% |

|

No |

92 |

17.0% |

|

Uncertain |

104 |

19.2% |

|

Perception of safety in the surrounding environment |

||

|

Strongly disagree |

25 |

4.6% |

|

Disagree |

50 |

9.2% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

49 |

9.1% |

|

Agree |

286 |

52.9% |

|

Strongly agree |

131 |

24.2% |

|

Total |

541 |

100.0% |

Source: Prepared by the author.

Hypothesis Testing

Table 3 shows the hypothesis testing of the work-related factors (x1, x2, x3,...,x13) related to the level of occupational stress and shows a significant association between factors incentives (p < 0.001), type of contract (p < 0.001), compensation (p < 0.001) and job stability (p < 0.001) and the level of occupational stress. On the contrary, factors such as type of activity (p = 0.719), work status (p = 0.843), time working (p = 0.452), shift rotation (p = 0.103), frequency of supervisions (p = 0.238), working hours (p = 0. 374), type of line of work (p = 0.081), significance of the task (p = 0.830) and perception of the safety of the surrounding environment (p = 0.531) are not significantly associated with the level of occupational stress.

H0: There is no significant association between work-related factors (x1, x2, x3,...,x13) and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima.

H1: There is a significant association between work-related factors (x1, x2, x3,...,x13) and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima.

α = 5% significance level

Table 3. Testing of Specific Hypotheses for Work-Related Factors and the Level of Occupational Stress.

|

Specific Hypotheses* |

Work-Related Factor |

Chi-Square |

|

p** |

|

Ha1 |

Type of activity |

1.341 |

|

0.719 |

|

Ha2 |

Work status |

2.725 |

|

0.843 |

|

Ha3 |

Time working |

5.75 |

|

0.452 |

|

Ha4 |

Shift rotation |

10.558 |

|

0.103 |

|

Ha5 |

Frequency of supervisions |

11.58 |

|

0.238 |

|

Ha6 |

Incentives |

39.553 |

|

<0.001 |

|

Ha7 |

Working hours |

9.71 |

|

0.374 |

|

Ha8 |

Type of contract |

30.147 |

|

<0.001 |

|

Ha9 |

Compensation |

77.134 |

|

<0.001 |

|

Ha10 |

Type of business where you work |

15.378 |

|

0.081 |

|

Ha11 |

Significance of the task |

7.398 |

|

0.830 |

|

Ha12 |

Job stability |

209.079 |

|

<0.001 |

|

Ha13 |

Perception of safety in the surrounding environment |

10.974 |

|

0.531 |

Source: Prepared by the author.

(*) Specific alternative hypotheses to be tested, with a significance level or type I error (α = 0.05).

(**) p-value of the statistical test.

DISCUSSION

Today, the world we live in is undergoing various changes that have an impact on work activities, labor relations and organizations, which are also constantly undergoing changes. Such changes create new psychosocial risks, but also new opportunities for professional, personal and social development.

Work environments are no stranger to this period of changes, which may affect the employees of an organization and, consequently, its productivity. According to ILO figures as of 2019, occupational stress affected 60% of the working population, and is therefore a cause for concern for company managers due to its adverse effects on the health of workers (Vidal, 2019).

According to the results obtained on the level of occupational stress in agents and supervisors of a security company in Lima, 63.8% have a low level of stress and 18.3% have a low medium level. Similar results were obtained by Pineda (2019) in his study on the level of anxiety and stress at work in surveillance workers, with 62.3% reporting mild psychological stress and 61.2% reporting mild or low physiological stress. Consistent similar results were obtained by Chipoco et al. (2018), as 77.0% of workers in a customs agency in Callao reported low levels of stress.

Other authors such as Bedoya et al. (2017) reported that 60.7% of staff members of the Police Unit of the Technical Investigation Corps of the city of Guadalajara had a low to very low level of occupational stress. Meanwhile, Vidal (2019) also observed mostly low level of stress in workers of SMEs (46.3%). However, these results are not consistent with those reported by Márquez and Flores (2019), who found that 89.4% of nurses in the emergency area of a health center in Arequipa experienced a medium level of occupational stress. In turn, Braganza (2018) found high levels of stress in employees of a public transit agency in Ambato, Ecuador.

Upon evaluating the level of occupational stress and work-related factors, it was determined that incentives (p < 0.001), type of contract (p < 0.001), compensation (p < 0.001) and job stability (p < 0.001) were significantly associated with the level of occupational stress of the agents and supervisors of the private security company in Lima. In other words, the lack of incentives, the lack of an indeterminate contract, the low level of compensation and the lack of job stability were associated with a severe level of occupational stress. These findings are consistent with those of Pineda (2019) regarding the low economic income or compensation related to a high level of psychological stress (p < 0.001). Furthermore, a propensity for occupational stress severity has been identified in security agents and supervisors whose work schedule exceeds 8 hours, which is consistent with the findings of Pineda (2019) who found a significant relationship between work schedules longer than 8 hours (p < 0.001) and severe physiological stress. However, Ahumada et al., (2011) observed that the severity of occupational stress is not related to longer working hours (p = 0.607).

Additional findings of this research included work-related factors not significantly associated with occupational stress, but that were associated with a certain degree of severity of occupational stress, such as the type of activity for entrance control with exposure to people, the work status as a stand-in guard or on call guard, and those with little time working in the security company. Likewise, security workers with less shift rotations and those supervised with greater continuity, who feel under heavy control, exhibited a certain degree of severity in the level of occupational stress.

It was observed that those security agents and supervisors who work in the industrial sector or warehouses presented a certain degree of severity of occupational stress, which does not correspond to the findings reported by Vidal (2019), who found that workers in the service sector have a higher level of occupational stress followed by those working in the industrial sector.

Based on the findings of this research, there are certain work-related factors that should be addressed as a priority, as they may be posing psychosocial risks in security agents and supervisors, especially, in the context of the covid-19 pandemic. It is necessary to adopt certain measures or strategies to prevent this situation, as it has an impact on the mental health of the workers and, consequently, on their work performance and productivity.

CONCLUSIONS

Upon evaluating the level of occupational stress and work-related factors, it was determined that factors incentives (p < 0.001), type of contract (p < 0.001), compensation (p < 0.001) and job stability (p < 0.001) were significantly associated with the level of occupational stress found in the participants of the study.

There is no significant relationship between the type of activity and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 1.341; p = 0.719).

There is no significant relationship between work status and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 2.725; p = 0.843).

There is no significant relationship between the time working and the level of occupational stress of the agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 5.750; p = 0.452).

There is no significant relationship between shift rotation and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 10.558; p = 0.103).

There is no significant relationship between the frequency of supervision and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 11.580; p = 0.238).

There is a significant relationship between the incentives and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 39.553; p < 0.001). Thus, occupational stress severity (medium high stress and high stress) is associated with the lack of incentives.

There is no significant relationship between work schedule and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 9.710; p = 0.370).

There is a significant relationship between the type of contract and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 30.147; p < 0.001). Thus, occupational stress severity (medium high stress and high stress) is associated with having a contract for a short or seasonal period.

There is a significant relationship between compensation and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 77.134; p < 0.001). Thus, occupational stress severity (medium high stress and high stress) is associated with a low level of remuneration.

There is no significant relationship between the type of business and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 15.378; p = 0.081).

There is no significant relationship between the significance of the task and the level of occupational stress of the agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 7.398; p = 0.830).

There is a significant relationship between job stability and the level of occupational stress of agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 209.079; p < 0.001). Thus, occupational stress severity (medium high stress and high stress) is related to an uncertain or non-existent job stability.

There is no significant relationship between the perception of security in the surrounding environment and the level of occupational stress of the agents and supervisors of a private security company in Lima (chi-square = 10.974; p = 0.531).

Programs should be implemented to develop workers’ competencies, measures should be taken to avoid mental and physical overload, active breaks should be implemented, tasks should be assigned according to the worker’s experience and knowledge, monotonous work should be avoided, schedules compatible with the workers’ private lives should be chosen, better communication between superiors should be established, forms of intimidation, violence, etc., should not be allowed, workers’ ideas should be welcomed, training should be provided to self-identify risks related to stress, among others.

The acknowledgment of certain work-related factors that may limit the performance of security agents and supervisors would improve the work environment, increase workers’ satisfaction and prevent absenteeism due to health problems, thus resulting in an economic benefit for the organization.

REFERENCES

[1] Ahumada, L., Uribe, C., Alba, A., & Zea, J. (2011). Relación del estrés laboral con las condiciones de trabajo y las características sociodemográficas de trabajadores en la central de comunicaciones de una empresa de taxis. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología, 8(1), 59-76. https://bit.ly/3Hcdm5G

[2] Bedoya, A., Jiménez, L., & Morales, J. (2017). Relación entre las condiciones de trabajo y el nivel de estrés laboral en la Unidad de Policía Judicial del Cuerpo Técnico de Investigación de la ciudad de Guadalajara de Buga. (Undergraduate thesis). Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios, Guadalajara de Buga. https://bit.ly/3G6yhpt

[3] Braganza, A. (2018). Estrés Laboral y Riesgos Psicosociales en el personal de la Agencia Nacional de Tránsito. (Master thesis). Universidad Técnica de Ambato, Ambato. https://bit.ly/3rV9cc2

[4] CERTUS (2021, 25 de junio). ¿Sabías que existen diversos tipos de contratos laborales en el Perú? https://bit.ly/3H0ZiMe

[5] Comisión Europea. (2000). Guía sobre el estrés relacionado con el trabajo: ¿La «sal de la vida» o «el beso de la muerte»? Oficina de Publicaciones.

[6] Condo, A., & Turpo, L. (2019). Factores laborales de la rotación de personal externa en la empresa El Tablón Food Center E.I.R.L. Arequipa, 2018. (Undergraduate thesis). Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa, Arequipa. https://bit.ly/3o3E7lj

[7] Chiavenato, I. (2009). Gestión del talento humano (3ª ed.). Distrito Federal, México: McGraw-Hill/Interamericana Editores S.A.

[8] Chipoco, J., Flores, A., Torres, L., & Varea, U. (2018). Felicidad y Estrés Laboral de los trabajadores en una agencia de Aduanas del Callao. (Master thesis). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima. https://bit.ly/3KPupwM

[9] De la Torre, D. (2019). Factores laborales y nivel de estrés laboral en docentes de la I.E.P. “San Antonio María Claret” de Huancayo, 2018. (Undergraduate thesis). Universidad Continental, Huancayo. https://bit.ly/3IGU6gR

[10] Ezquerra, L. (2006). Tiempo de trabajo: duración, ordenación y distribución. Barcelona, España: Editorial Atelier.

[11] Hummelsheim, D., Hirtenlehner, H., Jackson, J., & Oberwittler, D. (2010). Social Insecurities and Fear of Crime: A Cross-National Study on the Impact of Welfare State Policies on Crime-related Anxieties. European Sociological Review, 27(3), 327-345. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq010

[12] Márquez, E., & Flores, L. (2019). Las condiciones de trabajo y su relación con el estrés laboral de las enfermeras del servicio de emergencias del hospital de apoyo, Camaná, 2018. (Thesis). Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa, Arequipa. https://bit.ly/3rUMTTF

[13] Organización Internacional del Trabajo (2016). Estrés en el trabajo. Un reto colectivo (1ª ed.). https://bit.ly/33NsrMM

[14] Organización Mundial de la Salud (2004). La organización del trabajo y el estrés. Estrategias sistemáticas de solución de problemas para empleadores, personal directivo y representantes sindicales.

[15] Palma, S. (2005). Manual de la Escala de Satisfacción Laboral (SL-SPC). Lima, Perú: Editora y Comercializadora Cartolan E. I. R. L.

[16] Pineda, A. (2019). Nivel de Ansiedad y Estrés Laboral en Trabajadores de Vigilancia Privada asociados a características laborales. (Undergraduate thesis). Universidad Privada de Tacna, Tacna. https://bit.ly/3r5R3ZN

[17] Quiñones, C., & Rodríguez, S. (2015). La reforma laboral, la precarización del trabajo y el principio de estabilidad en el empleo. Revista latinoamericana de derecho social, (21), 179-201. https://bit.ly/3H7Jrvk

[18] Robbins, S., & Judge, T. (2009). Comportamiento organizacional (13ª ed.). Naucalpan de Juárez, México: Pearson Educación.

[19] Serrano, A. (2004). El entorno físico del trabajo. Gestión Práctica de Riesgos Laborales, (4), 16-21. https://bit.ly/3s0zEBc

[20] Suárez, R., Campos, L., Villanueva, J., & Mendoza, C. (2020). Estrés laboral y su relación con las condiciones de trabajo. Revista Electrónica de Conocimientos, Saberes y Prácticas, 3(1), 104-119. https://doi.org/10.5377/recsp.v3i1.9794

[21] Suárez, A. (2013). Adaptación de la Escala de estrés Laboral de la OIT-OMS en trabajadores de 25 a 35 años de edad de un Contact Center de Lima. Revista Científica Digital de Psicología PsiqueMag, 2(1), 33-50.

[22] Vidal, V. (2019). Estudio del estrés laboral en las PYMES en la provincia de Zaragoza. Revista de la Asociación Española de Especialistas en Medicina del Trabajo, 28(4), 254-267. https://bit.ly/3cL8V4i